With electrification upon us, we ask the experts if there’s still hope for characterful powertrains in an electric car world

Electrified powertrains are making their way into every corner of the car market and the end would now seem to be in sight for new combustion engined cars. To find out just what this means for the future of the driver’s car, we spoke to the people that know best.

What is the best package for a next-generation small performance car such as a hot hatch: BEV (Battery Electric Vehicle), HEV (Hybrid Electric Vehicle), PHEV (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle), or FCV (Fuel Cell Vehicle)?

Dr Frank Welsch, board member for technical development at Volkswagen: ‘PHEV is currently the best solution; it can drive with zero local emissions, has the advantage of lower maintenance costs, and also offers very good performance values with its two drives. The new Golf GTE has a system output of 180kW [242bhp], for example. That puts it on exactly the same performance level as the GTI.’

Richard Moore, propulsion director at Lotus: ‘It could be BEV or HEV. HEV gives the instant torque benefits of an EV plus the range performance of an ICE [Internal Combustion Engine]. For cost and packaging HEV is better than PHEV. The obvious trade between these two is that an HEV’s battery is charged from fossil-fuelled ICE and not from renewables. If it’s BEV this is dependent upon electrochemistry development in order to deliver the right entry price.

> BMW i3 review – the city car perfected?

Giles Muddell, chief engineer of advanced technology at Prodrive: ‘It may well be predominantly ICE-based with increasing levels of hybridisation to meet emissions requirements. Initially this is likely to be a 48V mild-hybrid, moving to PHEV. The generation after that is likely to be BEV, as we see increasing levels of pure electric vehicles come onto the market.’

Phil Hopwood, head of engine and emissions control products at Ricardo Automotive and Industrial: ‘We should expect both electrified ICE and BEV-powered hot hatches in the future. The package with the best mix of customer attributes, including cost, is likely to be a mild-hybridised ICE, though this would increase the manufacturer’s fleet average CO2. A high-voltage HEV powertrain will improve CO2 and performance feel via instant electric power, but will be higher cost and more suited to premium brands. The competitiveness of EV options will depend greatly on continued reduction in the cost of batteries and purchase tax incentives.’

Can a BEV be made as engaging as an ICE vehicle?

‘Yes, most definitely,’ says Moore. ‘Instant torque, twin electric motors for optimum torque vectoring in corners, plus active noise for driver experience and pedestrian safety.’ Hopwood agrees: ‘In terms of performance feel and power delivery, a higher-powered BEV is a highly competitive product. They do lose out with the lack of sporty noise. Ricardo is developing augmented sound for both ICE and BEV to increase noise level and quality and to mask undesirable noises.’

‘Noise is a big part of the driving experience and will not form part of the EV experience unless it is contrived by the manufacturer,’ says Muddell. He says that acceleration will be less engaging and more ‘expected’ like braking performance. ‘Torque will not progress in the way it does with an IC engine and you can no longer engage with the response of the vehicle through gear selection. However, BEV throttle response can be almost instantaneous.’

‘There are many situations where a BEV is clearly better than a combustion engine,’ says Welsch. ‘Full torque right from the start, high efficiency and an enormous rpm range speak for themselves.’

What will bring down the battery weight penalty and restore some agility?

‘It is true that the additional weight of electric vehicles cannot be compensated by lightweight construction at the moment,’ says Welsch. ‘On the one hand, additional weight means that more energy is required for acceleration, on the other the additional mass generates more energy during brake energy recuperation. And the agility of the Volkswagen ID.3 is quite impressive.’

Hopwood sees benefits of battery mass too. ‘Batteries do add weight but this can be a help; the battery tends to be located low down which helps the centre of gravity. As chemistry improves, batteries could become lighter, but even if this enables a car maker to put less modules into a battery pack, would they? The question of agility is also interesting. If you ask EV drivers whether their experience of driving on the road is less agile, they would not agree.’

‘As battery technology improves, the energy density will improve,’ says Muddell. ‘That will bring down cost, weight and package volume too. Depending on the model, there will be a trade-off between weight and range. If the availability and speed of fast charging become greater, it is easy to see battery capacities not much greater than today, but a lot lighter. Smaller, lighter batteries stored under the floor will reduce yaw inertia and restore agility.’

Can the dynamic character of particular drivetrains be delivered by a BEV: nose-led fast hatch, front-engine/rear-drive saloon, mid-engined sports car, rear-engined sports car, etc, or will dynamics become homogenised?

‘There is the potential for dynamics to become homogenised as a consequence of BEV architecture, which typically sees 40 per cent increased mass within the wheelbase, narrowing the range of axle load distribution,’ says Dr David Shuttlewood, Ricardo’s dynamics technical specialist. And although a typical BEV will have weight distribution close to the 50/50 ideal, he says it won’t have the steering and dynamics of a 50/50 ICE saloon because of how the increased mass affects the yaw inertia: ‘The yaw inertia to mass ratio is lower than what we have historically understood to be in the sweet spot. In some respects, the BEV is more like a bloated mid-engined sports car and requires some tuning wizardry to make it behave in the manner we are familiar with.’

‘For mass-market hatchbacks, packaging efficiency is important,’ says Muddell. ‘The motor/transmission and power electronics will typically be up front and therefore drive the front. The real problem is how to provide the power with the current battery technology for a hot hatch. Across a hatchback range it’s likely we’ll see identical battery packs physically, but with differing capacities and therefore power. This will lead to range and power being closely associated, with hot hatchbacks also getting longer range as well as higher power.’

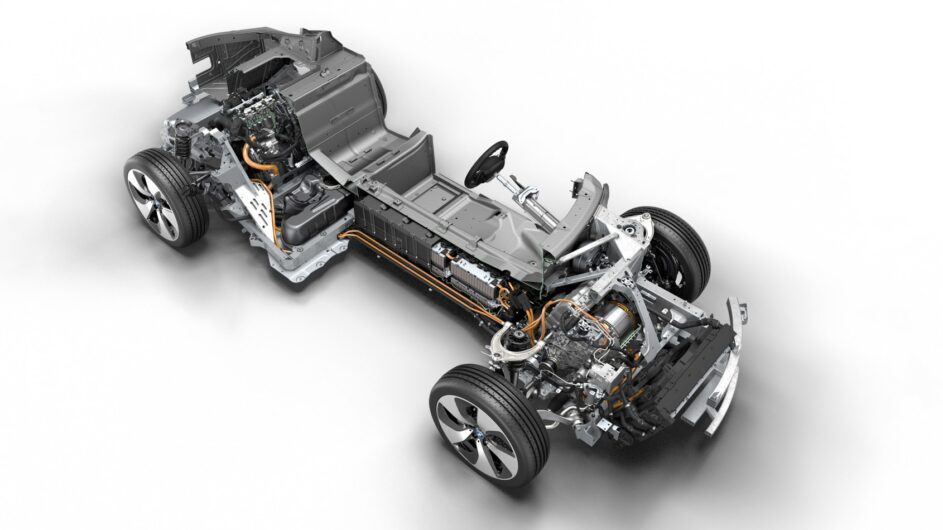

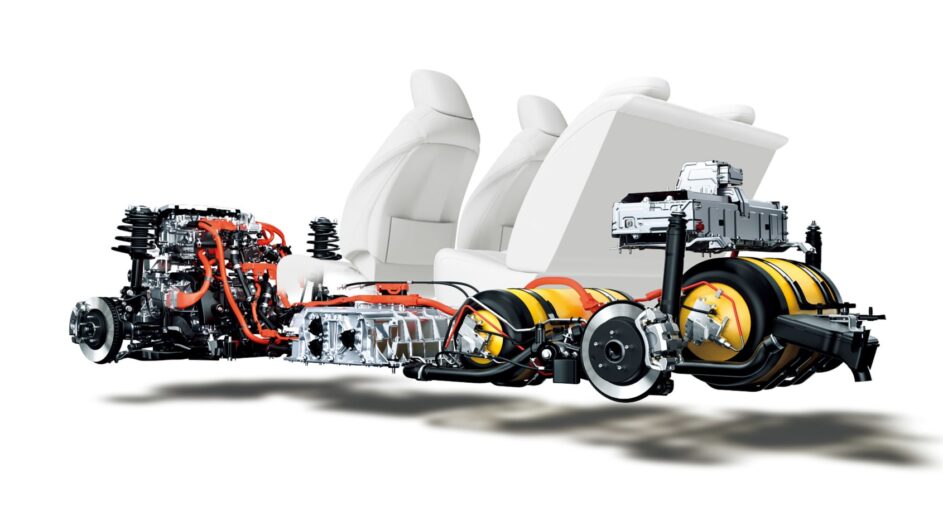

‘The character of front-, rear- and all-wheel-drive dynamics can be achieved via different Electric Drive Unit set-ups, and Lotus Engineering sees this as one of its core capabilities,’ says Moore. ‘Most relevant here is battery pack position and size, because this is a balance.’ With the battery as low as possible, the centre of gravity is reduced, but this increases occupant and vehicle height, he says. For the Evija hypercar, Lotus created a chest battery ahead of the rear axle that allows a lower vehicle set-up with most of the mass in the centre, just behind the occupants, ‘basically mimicking the position of the engine and gearbox of a mid-engined supercar’.

Do you think the Fuel Cell Vehicle will become a production reality?

‘Yes I do,’ says Moore. ‘The key is the safe transportation and storage of the fuel, and also infrastructure.’ However, most agree that future FCVs will be HGVs rather than cars. ‘The focus for development is currently within the commercial vehicle sector, particularly in heavy-duty trucks, where a BEV powertrain is challenged by cost, weight and range,’ says Hopwood.

‘Based on current knowledge, the fuel cell will not find any suitable use in the volume passenger car area,’ says Welsh. ‘However, we believe that it can be a worthwhile alternative for large and heavy vehicles driven over long distances.’

Will the fully autonomous car ever come to fruition, and if so, how long before that happens?

‘Autonomy will happen,’ says Muddell. ‘We already have most of the technology, but we need to prove it is reliable in its sensing and decision-making before we can give it to the public. I think the “low-hanging fruit” of automated motorway driving will happen first. Level 5 autonomy in cities is still a long way away. It’s difficult to say exactly when.’ ‘I don’t think the major barrier is technology maturity,’ says Moore. ‘It’s system, product and situation responsibility.’ This will probably take more time to sort out than the enabling technology, he adds.

‘Ricardo is working on projects with low-level autonomy and others that assume fully autonomous urban vehicles will be widespread by 2035,’ says Shuttlewood. ‘Key to the latter is a move away from outright vehicle ownership to a mobility service model.’ He says the technologies will be robust within this time frame and will improve safety, vehicle utilisation and reduce user costs, but adds that ‘their eventual take-up will depend on political and social factors’.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing