Steve McQueen, a showdown between Porsche’s 917 and Ferrari’s 512S, and one of the great drives

Today the only reason people remember the Sebring 12 Hours from 1970 is not for the Ferrari that won it, but the Porsche that did not. This is a travesty and on two counts: first, and for reasons we’ll get to in a minute, Ferrari’s win was a massively significant moment in the racing history of the Scuderia and one that came against all the odds; second, because of the credit taken by one of the drivers of the private Porsche for coming second. You will know his name: Terence Steven McQueen.

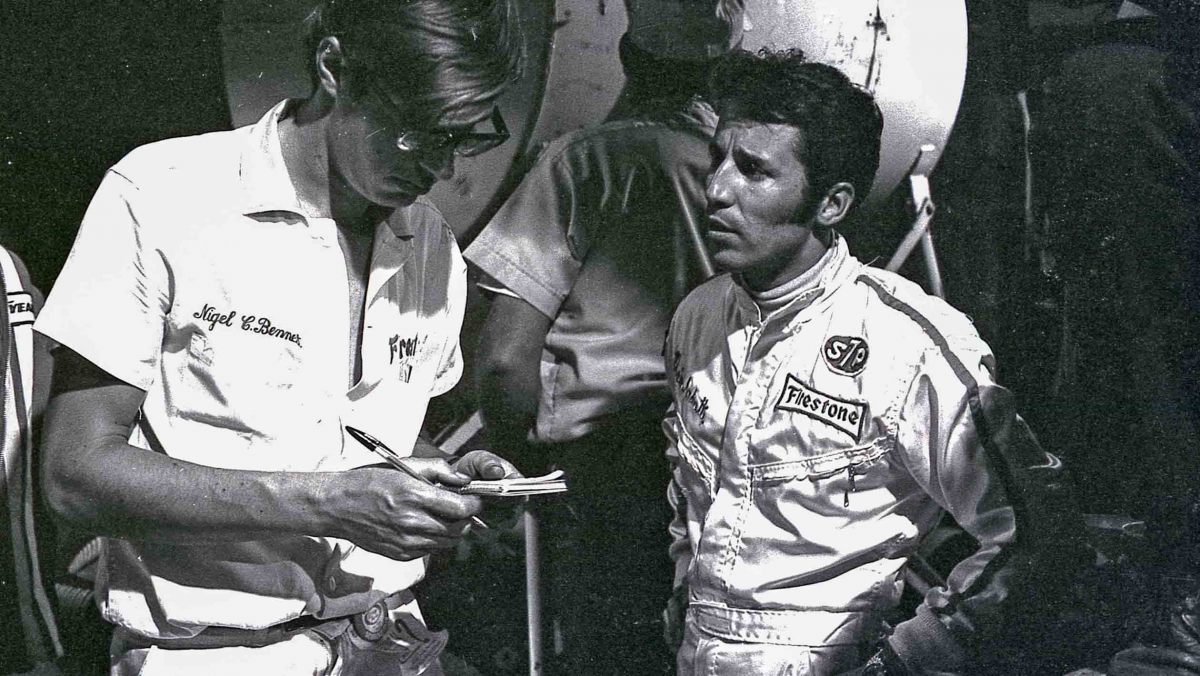

I’m not going to dwell on the Steve McQueen angle other than to set the record straight, which is that far from McQueen being the reason his Porsche 908 so nearly beat the Ferrari, he was the only reason it did not. Had he been anything like as good a driver as team-mate Peter Revson, they’d have walked it.

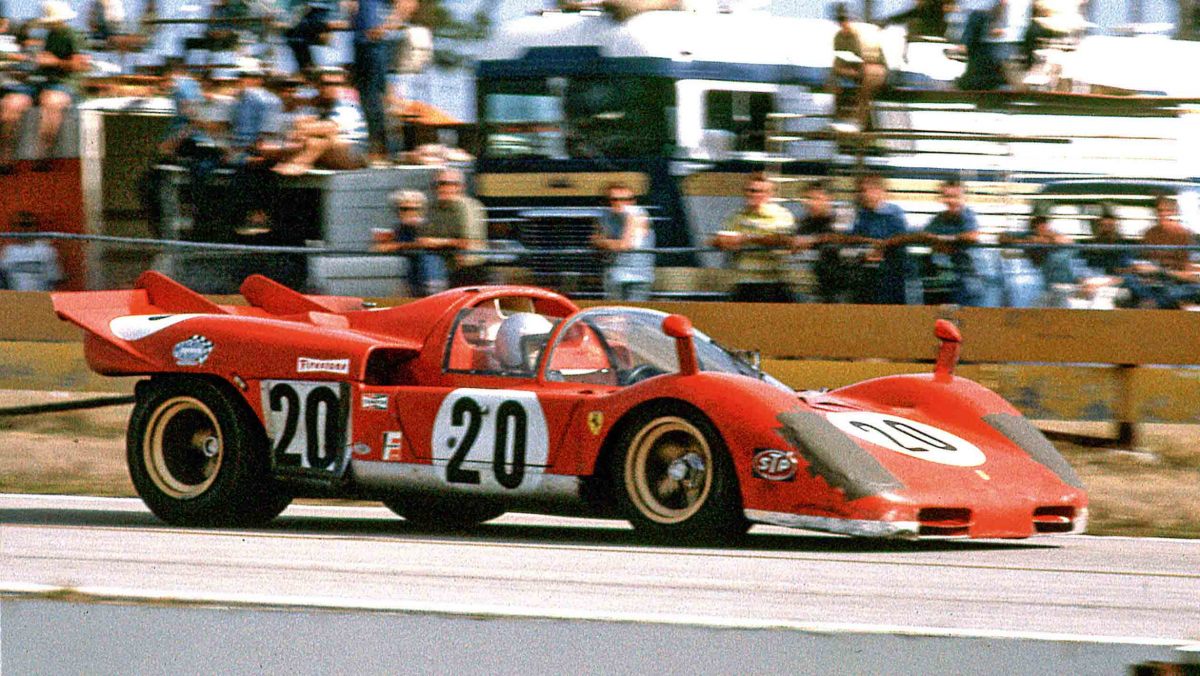

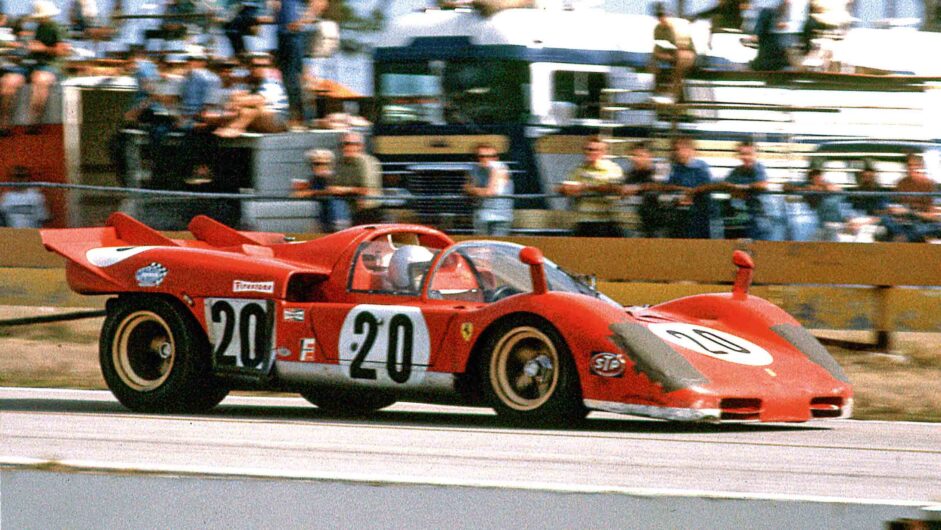

We will return shortly to how these cars even came to be in such close competition and why that win had significance far beyond Ferrari beating the film star, but first we need to look closer at the gorgeous, swooping shape of the Ferrari 512S, and how it got to be that way.

> Ferrari 250 GTO: the history, specs, prices and hype of an automotive icon

In a rush is the short answer. In 1968, the governing body then called the CSI introduced rules mandating a 3-litre limit for prototypes, meaning that if you wanted to race with a larger engine, you’d have to make 25 units: unthinkable for such space-age craft. Unthinkable to all except Porsche, which in 1969 stunned the racing world by lining up 25 identical 4.5-litre 917s for inspection. If Ferrari wished to continue in top-level sportscar racing, it had no choice but to respond.

But there were other problems: unlike Porsche, Ferrari also had an F1 team to run – and resources both financial and human were stretched. Worse, Ferrari was being bought by Fiat and no new race programme would be approved until that process was complete. The announcement came on June 21, 1969, giving Ferrari barely six months to design and engineer a new racing car, build 25 of them and sell some to privateers before the flag fell on the season’s opening race: the Daytona 24 Hours. Forget that the car turned out to be not quite a match for the 917: it was a miracle it got built at all. Indeed, the mandatory inspection of the 25 cars took place literally on the day of the last flight that would get the cars to Daytona on time, and even then Ferrari had to ask for the CSI’s understanding when it turned out that eight of the cars were in component rather than completed form…

In that timeframe there was no room for revolution. The car was new, but dictated by recent racing experience. The chassis would continue to be a spaceframe design clad with alloy sheets, conceptually similar to that already used in the 312P sportscar that had proven unequal to the challenge of Porsche’s 3-litre 908 during 1969, but in size and wheelbase it would split the difference between the 312P and the similarly unsuccessful 612P Can-Am car.

The engine would be loosely derived from the Can-Am V12, but narrower in bore, shorter in stroke and overall more over-square to displace 4994cc instead of 6222cc. Naturally it retained a four-cam, 48-valve head configuration and was good for 550bhp at 8000rpm, a 10 per cent improvement in horsepower per litre relative to the Can-Am unit. Lucas would provide mechanical fuel injection and Marelli the Dinoplex ignition. The engine would be carried as a semi-stressed unit and run through Ferrari’s own five-speed gearbox, directing its power via a ZF limited-slip differential. Suspension was of traditional double unequal-length

wishbone design at each corner, while Girling brakes were clamped by Ferodo pads behind Campagnolo wheels, 11in wide at the front and an enormous 16in wide at the back. That gorgeous body was fashioned largely from glassfibre.

Ferrari must have known it was going to have a struggle on its hands. The specific output of the new engine may have compared favourably to that of the Ferrari Can-Am car but, compared with the Porsche it was up against, it looked decidedly less clever. Despite being so closely based on the 908’s 3-litre flat-8 engine that it retained the same bore and stroke, the 917’s flat-12 was not only more powerful with 580bhp, it did so on a smaller 4.5-litre capacity despite having just two valves per cylinder.

But that wasn’t the real problem: a far larger headache was that thanks to exotic materials such as magnesium and titanium and such attention to detail that the gear-knob was crafted from balsa wood, the 917 weighed barely 800kg, the Ferrari an excessive 880kg. On paper, Ferrari’s 625bhp per tonne played Porsche’s 725bhp per tonne. On the track, that should have meant no contest.

That’s how it looked at Daytona. Ferrari had the previous year’s Indy 500 winner Mario Andretti, who duly put his 512S on pole, but the qualifying session was wet so not much could be read into that. Almost from the off, the two Gulf 917s led the field, chased by Andretti until the 512S’s real Achilles’ heel was revealed. After just 45 minutes, Andretti had drained his 120- litre Pirelli bag-tank and had to depart the battlefield for more fuel. The Porsches would go almost an hour. In the end it was a one/two finish for Porsche, Andretti’s car a sobering eight laps down on the winner. Of the other four 512S in the race, not one finished.

This did not augur well for Sebring, just seven weeks away. Sebring was a mere 12-hour race but, in racing circles, the bumpy old airfield track was such a car- killer it was often considered a more gruelling test of machinery than the 24 hours of Daytona or Le Mans. Ferrari did not waste a moment, testing extensively at Monza, ensuring the cars that went to Florida were already a little lighter, aerodynamically more efficient and with better fuel injection, which was said to improve power and reduce consumption.

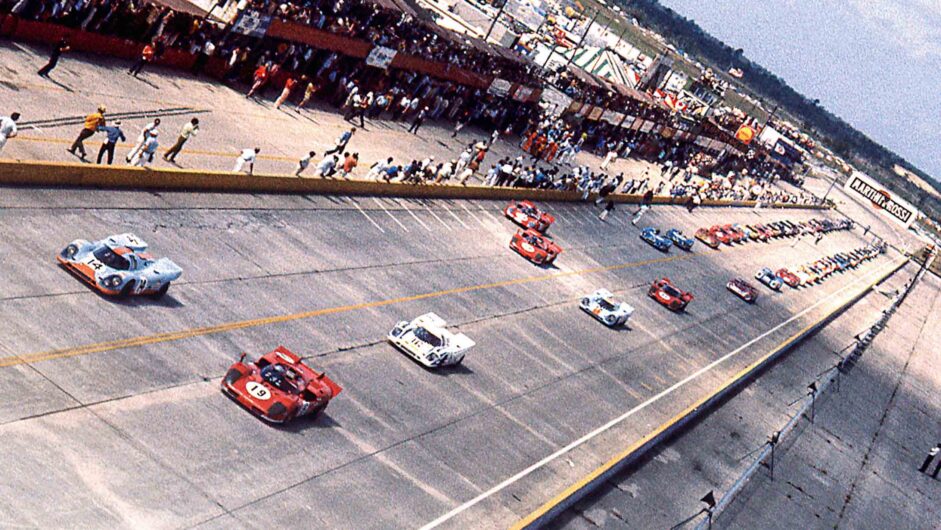

Andretti took pole again, but this time in a straight fight, beating the two quickest factory Porsches. However, the next best Ferrari of Jacky Ickx was fourth, while the third was down in seventh with Nino Vaccarella and Ignazio Giunti at the helm. An epic race was in prospect, and Sebring duly delivered.

There is not the space here to detail every plot twist that played in those dozen hours. Suffice to say that after the first hour it was already looking like a Porsche benefit, with 917s running in the first four places. But then two of the 917s were out, one with a blown engine, another with accident damage, while a third pitted for a lengthy stop with ignition issues. Three hours in and the pendulum had swung the other way and now it was three factory Ferraris holding all the podium places.

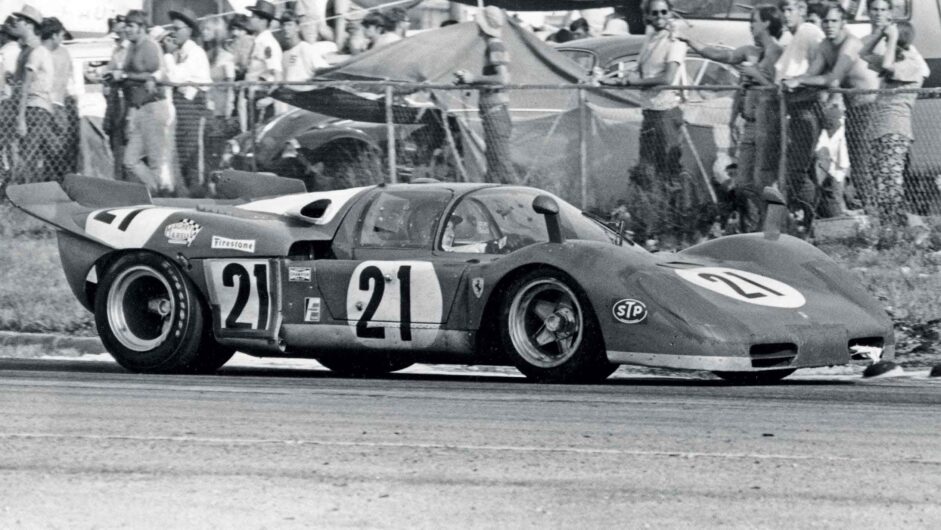

The status quo held until the middle of the race as the fightback by the Gulf 917s was hobbled by a duff batch of wheel bearings causing further delays. The only Porsche to continue untroubled was the private McQueen/Revson 908 that held position behind the Ferraris, although already many laps in arrears.

Then it all went wrong. First the head gasket blew on Ickx’s car, reducing the Ferrari assault by a third. Then the Vaccarella car got a puncture and damaged its suspension trying to hobble back to the pits for a long repair. All hope now seemed to lie with Andretti, who was kilometers out front with a double-digit lap lead over the best Porsche. Only it wasn’t now a 917 in second place, but McQueen’s 908…

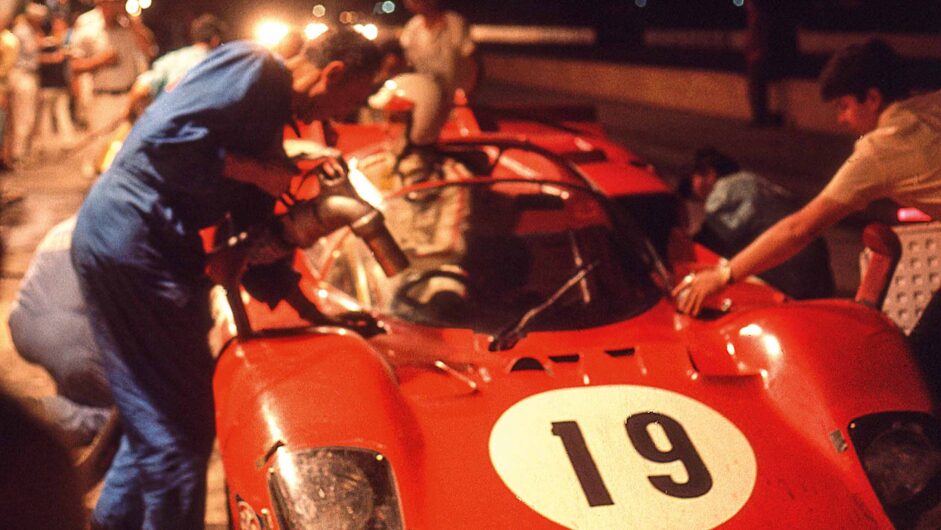

And then, with an hour to go, out in the inky darkness of the Florida night, the leading Ferrari’s gearbox let go. Worse, the recovering 917 of Jo Siffert had passed the McQueen car and now led the race. Porsches were now first and second, with an Alfa Romeo in third. Defeat seemed about to be snatched from the jaws of certain victory. A hero was needed. Fast.

With 55 minutes remaining (remember this number, as it’s important), Ferrari called in its remaining 512S – the fourth-placed Vaccarella car – and told its mightily unamused driver to give up his seat to Andretti.

The Alfa was easy meat, but the Porsches were far, far away. Mario has described what happened next as his greatest drive in a sportscar, routinely lapping four to six seconds faster than the car’s intended crew, hunting down an exhausted Peter Revson who’d done as much of McQueen’s driving as the regulations allowed. Mario caught and passed the 908 for second place with fewer than 30 minutes remaining. So second it would be.

Or would it? With under 20 minutes to go, the leading 917 suffered another hub failure and, while the car was repaired in double-quick time, it was now out of contention and finally Ferrari led once more. But even this was not the end to the drama, for the fact was that Andretti had departed the pits with 55 minutes remaining and the Ferrari hadn’t done 50 minutes on a tank of fuel all weekend…

Andretti not only had to come in but, as per the regulations at the time, switch off the engine and get out of the car. He said later that the moment he hit the ground, team manager Mauro Forghieri literally picked him up and threw him back in the car. He streaked back into the race as Revson was coming down the pit straight. He didn’t even have time to do up his belts. And, finally, that was that: after 12 hours of racing, the Ferrari 512S had won its first and, as it turned out, also its last round of the World Sportscar Championship, and by just 22sec. As for Andretti and those last few laps, he said: ‘Trying that hard, in a strange car, at night; only I will ever know the chances I took.’

There is a short and slightly sad coda to the story of the racing 512s. After Sebring, Porsche sorted out its iffy hubs and went on to dominate the championship. But, at the last round at the Österreichring, Ferrari revealed a car so heavily revised as to earn a new name: 512M, for modificata. It had much-revised aerodynamics, weight pared down to an almost 917-equalling 812kg, and an engine with chrome liners providing a 917-busting 616bhp.

Ickx qualified in second place despite fuelling issues and in the race proceeded to demolish the 917s, breaking his own outright lap record, despite the fact he’d set it just a few weeks earlier in his F1 Ferrari. But it was all for nothing: the alternator failed and the record books chalked up another win for the 917.

Which left just the season finale in South Africa, the Rand Nine Hours at Kyalami. And at last there was a straight fight to the finish: one factory 512M for Ickx and Giunti against one factory 917 for Jo Siffert and Kurt Ahrens. The result: pole position, fastest lap, fastest speed recorded on the straight and outright victory for Ferrari. At last, the 512 had proven its worth.

The sadness comes in two parts: first Kyalami wasn’t a championship round, so few remember it today. Secondly, despite having developed a car to conquer the 917, Enzo abandoned it immediately. New regs for 1972 mandated a 3-litre capacity so he knew the 512s would be obsolete within a season. Faced with this and an unfounded fear that Porsche was about to put a 16-cylinder engine in the 917 for 1971, he turned the 512M into a customer-only programme and focused on developing his 3-litre car instead. And it’s hard to argue he was wrong: the 312PB entered ten rounds of the 1972 series and won ten of them. It was the most successful and, as it would turn out, last factory-run sports racing prototype Ferrari would make.

This article originally appeared at evo.co.uk

Copyright © evo UK, Dennis Publishing